How to build a health registry?

The regulatory framework that accompanies the rapid growth in the use of technology in healthcare requires software to be designed, trained and validated using datasets that are representative of the population that will use the software: this requirement ensures not only that the software is effective, but also that bias is reduced.

In this sense, the new EU Reg. 2017/745 on medical devices in Annex XV on Clinical Investigations, point 3.6.3, states that the clinical investigation plan must contain (among others): ‘information on subjects, selection criteria, size of investigation population, representativeness of investigation population in relation to target population and, if applicable, information on vulnerable subjects involved such as children, pregnant women, immuno-compromised or, elderly subjects’.

In the same spirit, Art. 10(3) of the proposed AI regulation states as follows:

‘Training, validation and testing data sets shall be relevant, representative, free of errors and complete. They shall have the appropriate statistical properties, including, where applicable, as regards the persons or groups of persons on which the high-risk AI system is intended to be used. […]

Training, validation and testing data sets shall take into account, to the extent required by the intended purpose, the characteristics or elements that are particular to the specific geographical, behavioural or functional setting within which the high-risk AI system is intended to be used’.

The software sector therefore needs a large data set. It certainly needs to be lawful, accurate, clean, consistent, but also broad.

Thus, while awaiting the proposal for a Regulation on the Health Data Space (COM (2022) 197 of 3 May 2022) - which, as is well known, aims to create a large European repository of health data, also with a view to facilitating the re-use of data for secondary use - many public and private initiatives are being launched to create open databases for sharing health data.

Open data in healthcare

On this topic, the science journal Nature has recently published a very interesting article entitled 'A guide to sharing open healthcare data under the General Data Protection Regulation'.

The article analyses the approaches and processes that led to the collection of medical records from four intensive care units of different hospitals in the EU in order to create open databases.

The article is of great interest because it not only outlines four different approaches to open sharing of health data (each with different implications for data security, usability, sustainability and implementability), but also makes seven recommendations to guide similar initiatives.

Let's look at them briefly.

The four participating hospitals are AmsterdamUMCdb (Netherlands); HiRID (Switzerland); Sanitas Dat4Good (Spain); HM Hospital (Spain).

The project was carried out in all hospitals by a multidisciplinary team (doctors, IT, communication departments, data protection lawyers, ethicists, as well as third parties for the full analysis of the DPIA and to assess de-identification and governance strategies).

The legal basis

In terms of the legal basis to be used for the creation of the database, the choices were varied.

Apart from HiRID (Switzerland), which used consent, AmsterdamUMCdb, SANITAS and HM all collected data on the basis of Article 9(j) of the GDPR, considering consent to be an inappropriate legal basis and too complicated to handle.

De-identification

Once collected, the data underwent a de-identification process.

More specifically, SANITAS pseudonymised the dataset, removing only direct identifiers, and carried out a DPIA, which was then audited by an independent third-party.

The other three hospitals anonymised their database data instead.

HiRID performed anonymisation using the K method (a technique based on the concept that an anonymised individual must not be distinguishable from at least K-1 other individuals. In other words, if K=10, each individual must be indistinguishable from at least 9 other individuals).

AmsterdamUMCdb adopted a similar approach, but through an iterative process involving de-identification of data (through generalisation and suppression), then an assessment of the risk of re-identification by a third party, and if the outcome is not positive, an increase in the level of de-identification with further assessment by a third party[1].

Ethical evaluation

From the point of view of ethical evaluation, HiRID and AmsterdamUMCdb obtained a general opinion from the IRB (Institutional Review Board), whereas HM required a positive opinion for the establishment of the database and also required a specific positive ethical opinion from the party seeking access to the data.

Governance

Governance is also very interesting.

Each database has introduced a mandatory data request form, through which a scientific committee evaluates both the data applicant and the research proposal, thus preventing misuse of the data.

The four databases, which are regularly updated, are becoming a point of reference for those who need such data: by way of example, HiRID alone received more than 200 access requests per year and had 84 citations in original publications; HM received about 180 requests and approved 95% of them.

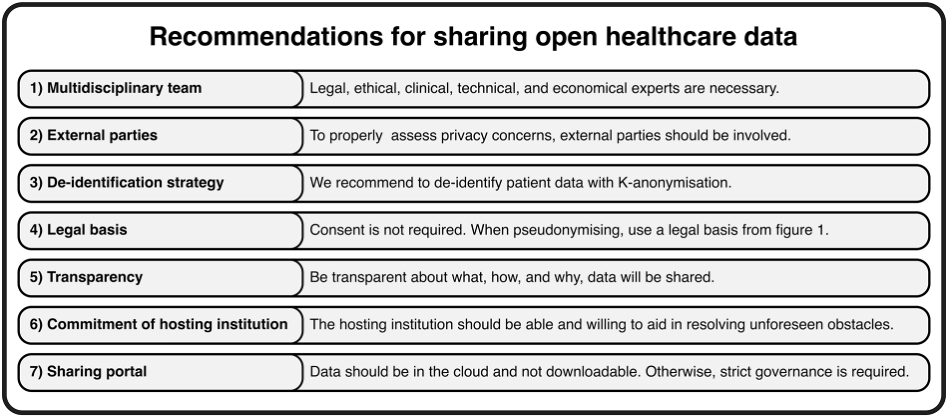

Finally, the article makes a number of recommendations that should be considered by those undertaking similar projects.

An outline of the recommendations is given below.

Conclusions

There is no doubt that open data is here to stay.

In early 2022, the US National Institute of Health (NIH) mandated that from 2023 all NIH-funded projects must include a 'data management and sharing plan' that makes their data publicly available; the Dutch research organisation ZonMw promotes open science and the 'FAIRification' of health research; and Stanford's AI Medicine and Imaging is expanding its free archive of datasets for researchers worldwide.

At the same time, the Data Governance Act (DGA)23 promotes data sharing and aims to create a trustworthy environment to facilitate innovative research and the production of innovative products and services: one of the key pillars of the DGA promotes data altruism across the EU, making it easier for individuals and companies to voluntarily share their data for the public good, e.g. for medical research projects.

However, this trend does not seem to apply in Italy.

Article 110 of the Privacy Code seems to prevent the use of any legal basis other than consent, and the positions of the Data Protection Authority (DPA) follow this trend.

Suffice it to think of the Opinion issued pursuant to art. 110 of the Code and art. 36 of the Regulation, on 30 June 2002, in response to a request from the Hospital of Verona, whose objective was to create a "registry" or "database" through "the collection of structured data that would allow the study of the population of patients suffering from neoplastic pathologies and in non-thoracic areas". In this case, the DPA set consent as the legal basis both for the creation of the database and for any subsequent studies that would be carried out by extracting data from the database.

In essence, a mechanism that makes the data registry complex to build and difficult to access.

Frankly, the same question arises again: are we really convinced that consent is the only way to ensure patient protection? Because if the answer is yes, we have to imagine that other countries (such as Spain) - which allow the use of Article 9(j) - are less protective of patients.

Or is it not time to consider that there may be other legal instruments that are just as lawful and protective, but can also facilitate research?